An update on More in Common's changes to our voting intention methodology from July 2023

Summary

- From July onwards, we will use an updated methodology to try more accurately allocate ‘don’t know’ respondents in our voting intention polls.

- Those who initially select ‘don’t know’ will be shown a follow-up question, prompting them again to select a party.

- Although ‘don’t know’ is still available as an option, around half of respondents now choose a party when prompted.

- These respondents are almost twice as likely to choose Conservative over Labour. This would have changed our June voting intention from a 19.4 point Labour lead, to 17.2 points.

- Our other filters – such as only including those who give a 7-10 likelihood to vote (to ensure we only capture ‘don’t knows’ who intend to vote) – will still apply.

How to treat those who respond ‘don’t know’ in voting intention polls is a challenge for pollsters. This group forms a sizeable segment of the public - in our latest More in Common polling they make up 18 per cent of all respondents, and 11 per cent of those who give a 7-10 likelihood of voting at the next election (a filter we apply to our voting intention polling to exclude those unlikely to vote). Many people don’t know how they are going to vote, particularly far from an election. However, ‘don’t know’ is not an option on the ballot paper, so pollsters have to decide if and how to factor them into their voting intention calculations.

A common method (and the one that More in Common has until now employed) is to treat those who say ‘don’t know’ the same way as those who say they wouldn’t vote, and to exclude them from the voting intention calculation. This is methodologically simple, easy to apply, and consistent. However, it also assumes that ‘don’t know’ respondents either will not vote or will vote in the same proportions as all voters at the next election. This is not necessarily the case, and calculating this way may distort voting intention figures.

This has become particularly important in the 2020s. The Conservative vote has fallen significantly in the last two years. Across several rounds of More in Common polling, barely half of 2019 Conservative voters say they still intend to vote for the party, with a large number saying they ‘don’t know’ how they will vote. In fact, 2019 Conservative voters are over five times as likely to select this option compared to 2019 Labour voters. Given that these voters are then excluded from the voting intention calculations, this could produce artificially high Labour leads. Equally, long-standing research from the US suggests that those who respond don’t know close to an election are much more likely to break for the challenger/opposition party. In this instance, excluding ‘don’t know’ voters could artificially deflate Labour leads close to the election.

Other pollsters have recognised this problem and made methodological changes to reflect it. Opinium notably weights up the 2019 Conservative voters who do give a voting intention to account for the fact that others are undecided. Kantar Public do not include a ‘don’t know’ option in their voting intention polling, only ‘prefer not to say’ or ‘would not vote’. They note that while most polling excludes ‘don’t know’ voters, given 2019 Conservative voters select this at a much greater rate, this assumes that they will be far less likely to vote than 2019 Labour voters – when historical data suggests their turnout likelihood is the same. Removing ‘don’t know’ as an option is one solution for this.

There is clearly no perfect way to divine voting intention from those who say they ‘don’t know’ how they will vote. However, from our July voting intention poll onwards (after testing and piloting in our June voting intention) we will use a slightly revised methodology to try and better capture the dynamics of those who say they ‘don’t know' would vote for if an election were held tomorrow. Instead of immediately excluding them, those who initially respond ‘don’t know’ will receive a 'squeeze' question – “If you were forced to choose, which party would you vote for?” - encouraging them to choose. Those who then indicate a vote choice will have their responses included as part of the overall calculations. Our usual other filters – such as only including those who indicate a 7-10 likelihood to vote – will still apply.

Note: we will still keep a ‘don’t know’ option available at this second stage. ‘Don’t know’ is a valid response when asking people how they intend to vote far from an election, and we want to avoid assigning people a party vote choice which wouldn’t represent them. We believe that prompting these respondents again to choose - but not forcing them - strikes the best balance.

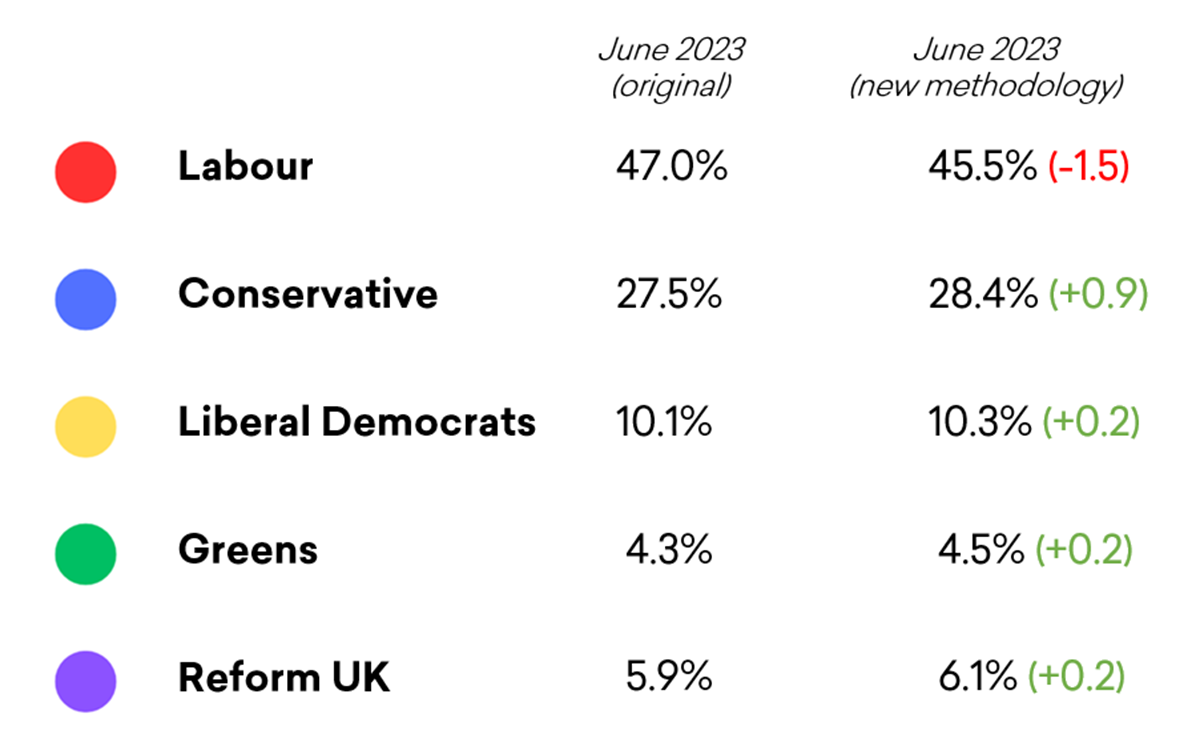

An pilot of this method - shown in the data tables for our June voting intention - led to the following result:

Of those who gave a 7-10 likelihood to vote and initially selected ‘don’t know’, over half then expressed a party vote choice after prompting. Incorporating this into our voting intention calculations, a 19.4 point Labour lead would have fallen to a 17.2 point one.

Although inclusion of a ‘squeeze’ question for voting intention is not new, these results show that it has renewed importance in the context of current UK voting intentions. Whereas it has been observed before that they had little effect – the BPC report on the 2015 General Election stating that “they had very little impact on the party vote shares for the samples as a whole, and no effect on the difference between the Conservative and Labour vote shares” – this is no longer the case. Our initial pilot of this method found that initial ‘don’t know’ respondents when prompted were almost twice as likely to choose the Conservatives over Labour.

Going forward, we will continue to include the raw data from all questions in our data tables so that those that wish to see the VI under the old methodology can do. However, it will be the second calculation – which includes the initial ‘don’t know’ respondents who then indicate a vote choice – which will be reported as our headline voting intention figure.

Further enquiries: tyron@moreincommon.com